此章节的主要内容分为三个部分,分别为进一步深入异常处理、命名空间、多重继承与虚继承

C++通过抛出(throwing)一条表达式来引发异常,当执行一个 throw 时,跟在 throw 后面的语句不再被执行,程序控制权将转移到与之匹配的 catch 模块。沿着调用链的函数可能会提早退出,一旦程序开始执行异常代码,则沿着调用链创建的对象将被销毁

如果在 try 内进行 throw 异常,则会寻找此 try 语句的 catch 是否有此异常与之匹配的捕获,如果没有将会转到调用栈的上一级,即函数调用链的上一级,try 的作用域内可以有 try,会向上级一层一层的找,如果到 main 还是不能捕获则将会除法标准库函数 terminate,即程序终止

//example1.cpp

void func2()

{

try

{

throw overflow_error(" throwing a error");

cout << "3 hello world" << endl;

}

catch (range_error &e)

{

cout << "1 " << e.what() << endl;

}

}

void func1()

{

try

{

func2();

}

catch (overflow_error &e)

{

cout << "2 " << e.what() << endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

func1(); // 2 throwing a error

return 0;

}如果异常没有被捕获,则它将终止当前的程序

在栈展开时,即当 throw 后离开某些块作用域时,能够自动释放的栈内存将会被释放,但是要保证申请的堆内存释放,推荐使用 shared_ptr 与 unique_ptr 管理内存

//example2.cpp

class Person

{

public:

int age;

Person(const int &age) : age(age)

{

}

~Person()

{

cout << "dis Person" << endl;

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

try

{

shared_ptr<Person> p(new Person(1));

throw runtime_error("m_error");

}

catch (runtime_error &e)

{

cout << e.what() << endl;

}

cout << "end" << endl;

//程序输出 dis Person m_error end

return 0;

}可见在 try 作用域离开时,其内部的对象的析构函数将会被调用,但是在析构函数中也是可能存在抛出异常的情况。约定俗成,构造函数内应该仅仅 throw 其自己能够捕获的异常,如果在栈展开的过程中析构函数抛出了异常,并且析构函数本身没有将其捕获,则程序将会被终止

//example3.cpp

class Person

{

public:

~Person()

{

throw runtime_error("");

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

try

{

Person person;

}

catch (runtime_error e)

{

cout << e.what() << endl;

}

//程序出发了terminate标准函数程序终止运行

return 0;

}编译器使用异常抛出表达式来对异常对象进行拷贝初始化,其确保无论最终调用的哪一个

catch 子句都能访问该空间,当异常处理完毕后,异常对象被销毁

如果一个 throw

表达式解引用基类指针,而指针实际指向派生类对象,则抛出的对象系那个会被切掉,只有基类部分被抛出

//example4.cpp

void func1()

{

try

{

runtime_error e("1");

throw e; //发生构造拷贝

}

catch (runtime_error &e)

{

cout << e.what() << endl; // 1

}

}

void func2()

{

try

{

runtime_error e("2");

throw &e; ////没有被处理之前其内存不会被释放

}

catch (runtime_error *e)

{

cout << e->what() << endl; // 2

}

}

void func3()

{

try

{

runtime_error e("3");

exception *p = &e;

throw p; //只抛出基类部分

}

catch (exception *e)

{

cout << e->what() << endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

func1(); // 1

func2(); // 2

func3(); // 3

cout << "end" << endl; // end

return 0;

}使用 catch 子句对异常对象进行捕获,如果 catch

无须访问抛出的表达式,则可以忽略形参的名字,捕获形参列表可以为值类型、左值引用、指针,但不可为右值引用

抛出的派生类可以对 catch

的基类进行初始化、如果抛出的是非引用类型、则异常对象将会切到派生类部分,最好将

catch 的参数定义为引用类型

如果在多个 catch 语句的类型之间存在继承关系,则应该把继承链最底端的类放在前面,而将继承链最顶端的类放在后面

//example5.cpp

void func1()

{

try

{

throw runtime_error("1");

}

catch (exception &e)

{

cout << "1 exception" << endl;

}

catch (runtime_error &e)

{

cout << "1 runtime_error" << endl;

}

} //输出 1 exception

void func2()

{

try

{

throw runtime_error("2");

}

catch (runtime_error &e)

{

cout << "2 runtime_error" << endl;

}

catch (exception &e)

{

cout << "2 exception" << endl;

}

} // 2 runtime_error

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

func1(); // 1 exception

func2(); // 2 runtime_error

return 0;

}重新抛出就是在 catch 内对捕获的异常对象又一次抛出,有上一层进行捕获处理,重新抛出的方法就是使用 throw 语句,但是不包含任何表达式,空的 throw 只能出现在 catch 作用域内

//example6.cpp

void func1()

{

try

{

throw runtime_error("error");

}

catch (runtime_error &e)

{

throw; //重新抛出

}

}

void func2()

{

try

{

func1();

}

catch (runtime_error &e)

{

cout << "2 " << e.what() << endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

func2(); // 2 error

return 0;

}有时在 try 代码块内有不同类型的异常对象可能被抛出,但是当这些异常发生时所需要做出的处理行为是相同的,则可以使用 catch 对所有类型的异常进行捕获

//example7.cpp

void func()

{

static default_random_engine e;

static bernoulli_distribution b;

try

{

bool res = b(e);

if (res)

{

throw runtime_error("error 1");

}

else

{

throw range_error("error 2");

}

}

catch (...)

{

throw;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < 10; i++)

try

{

func();

}

catch (range_error &e)

{

cout << e.what() << endl;

}

catch (...)

{

cout << "the error is not range_error" << endl;

}

// the error is not range_error

// the error is not range_error

// the error is not range_error

// error 2

// error 2

// error 2

// the error is not range_error

// error 2

// the error is not range_error

// the error is not range_error

return 0;

}构造函数中可能抛出异常,构造函数分为两个阶段,一个为列表初始化过程,和函数体执行的过程,但是列表初始化时产生的异常怎样进行捕获呢?

需要写成函数 try 语句块(也成为函数测试块,function try

block)的形式

要注意的是,函数 try 语句块 catch

捕获的是列表中的错误,而不是成员初始化过程中的错误

//example8.cpp

class A

{

public:

shared_ptr<int> p;

A(int num)

try : p(make_shared<int>(num)) //当初始化列表中的语句执行抛出异常时

{

//或者函数体抛出异常时 下方catch都可以将其捕获

}

catch (bad_alloc &e)

{

cout << e.what() << endl;

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A a(12);

return 0;

}构造函数 try 语句会将异常重新抛出

//example9.cpp

class A

{

public:

A()

try

{

throw runtime_error("error1");

}

catch (runtime_error &e)

{

cout << e.what() << endl;

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

try

{

A a; // error1

}

catch (runtime_error &e)

{

cout << "main " << e.what() << endl; // main error1

}

return 0;

}同样可以用于析构函数

//example10.cpp

int func()

{

throw runtime_error("func");

return 1;

}

class A

{

public:

int num;

A()

try : num(func())

{

}

catch (runtime_error &e)

{

cout << e.what() << endl; // func

}

~A() //可用于析构函数,捕获函数体内的异常

try

{

}

catch (...)

{

cout << "~A error" << endl;

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

try

{

A a;

}

catch (runtime_error &e)

{

cout << "main " << e.what() << endl; // main func

}

return 0;

}noexcept 可以提前说明某个函数不会抛出异常,可以在函数指针的声明、定义中指定 noexcept。不能在 typedef 或类型别名中出现 noexcept。在成员函数中,noexcept 跟在 const 及引用限定符之后、在 final、overrride 或虚函数的=0 之前

虽然指定 noexcept,但是仍可以违反说明,如果违反则会触发 terminate

//example11.cpp

void func() noexcept

{

throw runtime_error(""); // warning: throw will always call terminate()

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

func();//会触发terminate

return 0;

}异常处理是C++语言的重要特性,在C++11标准之前,我们可以使用throw(optional_type_list)声明函数是否抛出异常,并描述函数抛出的异常类型。理论上,运行时必须检查函数发出的任何异常是否确实存在于optional_type_list中,或者是否从该列表中的某个类型派生。如果不是,则会调用处理程序std::unexpected。但实际上,由于这个检查实现比较复杂,因此并不是所有编译器都会

遵从这个规范。此外,大多数程序员似乎并不喜欢throw(optional_type_list)这种声明抛出异常

的方式,因为在他们看来抛出异常的类型并不是他们关心的事情,他们只需要关心函数是否会抛出异常,

即是否使用了throw()来声明函数。

// g++ main.cpp -o main.exe --std=c++98

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

using namespace std;

void func() throw()

{

// 声明了throw()但是抛出了异常,会直接core

throw std::runtime_error("hi mom");

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

try

{

func();

}

catch(const std::exception& e)

{

// 此处并入会进入,因为func声明了throw()

std::cerr << e.what() << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}使用throw声明函数是否抛出异常一直没有什么问题, 直到C++11标准引入了移动构造函数。移动构造函数中 包含着一个严重的异常陷阱。

当我们想将一个容器的元素移动到另外一个新的容器中时。 在C++11之前,由于没有移动语义,我们只能将原始容器的数据 复制到新容器中。如果在数据复制的过程中复制构造函数发生了异常, 那么我们可以丢弃新的容器,保留原始的容器。在这个环境中, 原始容器的内容不会有任何变化。

但是有了移动语义,原始容器的数据会逐一地移动到新容器中, 如果数据移动的途中发生异常,那么原始容器也将无法继续使用, 因为已经有一部分数据移动到新的容器中。这里读者可能会有疑问, 如果发生异常就做一个反向移动操作,恢复原始容器的内容不就可以了吗? 实际上,这样做并不可靠,因为我们无法保证恢复的过程中不会抛出异常。

这里的问题是,throw并不能根据容器中移动的元素是否会抛出异常来 确定移动构造函数是否允许抛出异常。针对这样的问题, C++标准委员会提出了noexcept说明符。

noexcept是一个与异常相关的关键字,它既是一个说明符, 也是一个运算符。作为说明符,它能够用来说明函数是否会抛出异常, 例如:

// --std=c++11

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <stdexcept>

class MyObject

{

public:

// 移动构造函数使用了 noexcept

MyObject(MyObject &&other) // noexcept

{

// 如果因为加了throw如果抛出异常外面的try{}则无法捕获到异常

// throw std::runtime_error("hi mom");

this->n = std::move(other.n);

other.n = 0;

this->str = std::move(other.str);

}

MyObject() = default;

MyObject(const MyObject &) = default;

MyObject &operator=(const MyObject &) = default;

int n;

std::string str;

};

int main()

{

try

{

std::vector<MyObject> originalVector;

MyObject object;

object.n = 1;

object.str = "hi mom";

originalVector.push_back(object);

originalVector.push_back(object);

originalVector.push_back(object);

// 移动构造函数使用了 noexcept,确保在移动过程中不会抛出异常

std::vector<MyObject> newVector(std::make_move_iterator(originalVector.begin()),

std::make_move_iterator(originalVector.end()));

//000

std::cout << originalVector[0].n << originalVector[1].n << originalVector[2].n << std::endl;

//""

std::cout << originalVector[0].str << originalVector[1].str << originalVector[2].str << std::endl;

//111

std::cout << newVector[0].n << newVector[1].n << newVector[2].n << std::endl;

//"hi momhi momhi mom"

std::cout << newVector[0].str << newVector[1].str << newVector[2].str << std::endl;

}

catch (const std::exception &e)

{

std::cerr << "Caught an exception: " << e.what() << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}throw()与noexcept其实都可以用

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

using namespace std;

struct X

{

int f() const throw()

{

throw std::runtime_error("hi mom");

return 888;

}

void g() noexcept

{

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

X x;

try

{

x.f();

x.g();

}

catch (...)

{

}

return 0;

}

/*

terminate called after throwing an instance of 'std::runtime_error'

what(): hi mom

已放弃(吐核)

*/以上代码非常简单,用noexcept声明了函数foo

以及X的成员函数f和g。指示编译器这几个函数

是不会抛出异常的,编译器可以根据声明优化代码。

请注意,noexcept只是告诉编译器不会抛出异常,

但函数不一定真的不会抛出异常。这相当于对编译器

的一种承诺,当我们在声明了noexcept的函数中抛出异常时,

程序会调用std::terminate去结束程序的生命周期。

noexcept(true)表示不会抛出异常、noexcept(false)表示可能抛出异常

//example12.cpp

void func() noexcept(true)

{

}

void func1() noexcept(false)

{

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

func();

func1();

return 0;

}另外,noexcept接受一个返回布尔的常量表达式,当表达式评估为true的时候, 其行为和不带参数一样,表示函数不会抛出异常。反之,当表达式评估为false的时候, 则表示该函数有可能会抛出异常。这个特性广泛应用于模板当中,例如:

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

using namespace std;

// template <class T>

// T copy(const T &o) noexcept

// {

// }

template <class T>

T copy(const T &o) noexcept(std::is_fundamental<T>::value)

{

return o;

}

struct X

{

X() = default;

X(const X &other)

{

throw std::runtime_error("hi mom");

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

int n = 1;

int n1 = copy(n);

cout << n << " " << n1 << endl;

try

{

X x;

auto x1 = copy(x); // X为非基础类型

}

catch (const std::exception &e)

{

std::cerr << e.what() << std::endl;

}

// 1 1

// hi mom

return 0;

}上面这段代码通过std::is_fundamental来判断T是否为基础类型,如果T是基础类型,

则复制函数被声明为noexcept(true),即不会抛出异常。反之,

函数被声明为noexcept(false),表示函数有可能抛出异常。

请注意,由于noexcept对表达式的评估是在编译阶段执行的,

因此表达式必须是一个常量表达式。

noexcept 是一个一元运算符,返回值为 bool 类型右值常量表达式

该过程是在编译阶段进行,所以表达式本身并不会被执行。而表达式的结果取决于编译器是否在表达式中找到潜在异常:

//example13.cpp

void func1() noexcept

{

}

void func2() noexcept(true)

{

}

void func3() noexcept(false)

{

throw runtime_error("");

}

void func4() noexcept

{

func1();

func2();

};

void func5(int i)

{

func1();

func3();

}

//混合使用

void func6() noexcept(noexcept(func5(9)))

{

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

cout << noexcept(func1()) << endl; // 1

cout << noexcept(func2()) << endl; // 1

cout << noexcept(func3()) << endl; // 0

cout << noexcept(func4()) << endl; // 1

//当func4所调用的所有函数都是noexcept,且本身不含有throw时返回true 否则返回false

cout << noexcept(func5(1)) << endl; // 0

return 0;

}当编译器合成拷贝控制成员时,同时会生成一个异常说明,如果该类成员和其基类所有操作都为

noexcept,则合成的成员为 noexcept 的。不满足条件则合成

noexcept(false)的。

在析构函数没有提供 noexcept

声明,编译器将会为其合成。合成的为与编译器直接合成析构函数提供的

noexcept 说明相同。

noexcept运算符能够准确地判断函数是否有声明不会抛出异常。有了这个工具, 我们可以进一步优化复制函数模板:

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

using namespace std;

// 判断T的拷贝构造函数,如果拷贝构造函数加了noexcept则copy则也会声明noexcept

// try{}中直接coredump

template <class T>

T copy(const T &o) noexcept(noexcept(T(o)))

{

return o;

}

struct X

{

X() = default;

X(const X &other)

{

throw std::runtime_error("hi mom");

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

try

{

X x;

auto x1 = copy(x);

}

catch (const std::exception &e)

{

std::cerr << e.what() << std::endl;

}

cout << boolalpha << noexcept(int(1)) << noboolalpha << endl; // true

return 0;

}这段代码看起来有些奇怪,因为函数声明中连续出现了两个noexcept关键字, 只不过两个关键字发挥了不同的作用。其中第二个关键字是运算符, 它判断T(o)是否有可能抛出异常。而第一个noexcept关键字则是说明符, 它接受第二个运算符的返回值,以此决定T类型的复制函数是否声明为不抛出异常。

异常的存在对容器数据的移动构成了威胁, 因为我们无法保证在移动构造的时候不抛出异常。 现在noexcept运算符可以判断目标类型的移动构造函数是否有可能抛出异常。 如果没有抛出异常的可能,那么函数可以选择进行移动操作;否则将使用传统的复制操作。

下面,就来实现一个使用移动语义的容器经常用到的工具函数swap:

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

using namespace std;

void func1() noexcept

{

throw std::runtime_error("hi mom");

}

void func2() noexcept

{

func1();

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

try

{

func2();

}

catch(const std::exception& e)

{

std::cerr << e.what() << '\n';

}

return 0;

}这个就有问题,func1不可能抛出异常,func1异常则不可能到func2代码块中,main的catch更不可能捕获到。如果func1没有加noexcept什么都很正常,如果func2声明了noexcept那么写代码时其实也不用去try{func2()}了func2根本不会抛出异常。

swap函数:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

template <class T>

void swap(T &a, T &b) noexcept(noexcept(T(std::move(a))) && noexcept(a.operator=(std::move(b))))

{

static_assert(noexcept(T(std::move(a))) && noexcept(a.operator=(std::move(b))),

"noexcept(T(std::move(a))) && noexcept(a.operator=(std::move(b)))");

T tmp(std::move(a));

a = std::move(b);

b = std::move(tmp);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

string str1 = "hi mom";

string str2;

cout << str1 << endl; // "hi mom"

cout << str2 << endl; // ""

swap(str1, str2);

cout << str1 << endl; // ""

cout << str2 << endl; //"hi mom"

return 0;

}改进版的swap在函数内部使用static_assert对类型T的移动构造函数和移动赋值函数进行检查, 如果其中任何一个抛出异常,那么函数会编译失败。使用这种方法可以迫使类型T实现不抛出异常 的移动构造函数和移动赋值函数。但是这种实现方式过于强势,我们希望在不满足移动要求的时候, 有选择地使用复制方法完成移动操作。

最终版swap函数:

#include <iostream>

#include <type_traits>

using namespace std;

struct X

{

X() {}

X(X &&) noexcept {}

X(const X &) {}

X operator=(X &&) noexcept

{

return *this;

}

X operator=(const X &)

{

return *this;

}

};

struct X1

{

X1() {}

X1(X1 &&) {}

X1(const X1 &) {}

X1 operator=(X1 &&) { return *this; }

X1 operator=(const X1 &) { return *this; }

};

// 是noexcept则用移动语义

template <typename T>

void swap_impl(T &a, T &b, std::integral_constant<bool, true>) noexcept

{

T tmp(std::move(a));

a = std::move(b);

b = std::move(tmp);

cout << "move" << endl;

}

// 不是noexcept则用拷贝构造

template <typename T>

void swap_impl(T &a, T &b, std::integral_constant<bool, false>)

{

T tmp(a);

a = b;

b = tmp;

cout << "copy" << endl;

}

template <typename T>

void my_swap(T &a, T &b) noexcept(noexcept(swap_impl(a, b,

std::integral_constant<bool, noexcept(T(std::move(a))) && noexcept(a.operator=(std::move(b)))>())))

{

swap_impl(a, b,

std::integral_constant<bool, noexcept(T(std::move(a))) && noexcept(a.operator=(std::move(b)))>()

);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

X x1, x2;

my_swap(x1, x2); // move

X1 x3, x4;

my_swap(x3, x4); // copy

return 0;

}以上代码实现了两个版本的swap_impl,它们的形参列表的前两个形参是相同的,

只有第三个形参类型不同。第三个形参为std::integral_constant<bool, true>的函数会使用移动

的方法交换数据,而第三个参数为std::integral_constant<bool, false>的函数则会使用复制的

方法来交换数据。swap函数会调用swap_impl,并且以移动构造函数和移动赋值函数是否会抛出异常

为模板实参来实例化swap_impl的第三个参数。这样,不抛出异常的类型会实例化一个类型为

std::integral_constant<bool, true>的对象,并调用使用移动方法的swap_impl;反之则调用使用

复制方法的swap_impl。请注意这段代码中,我为了更多地展示noexcept的用法将代码写得有些复杂。

实际上noexcept(T(std::move(a))) && noexcept(a.operator=(std:: move(b)))这段代码完全可以

使用std::is_nothrow_move_constructible<T>::value && std::is_nothrow_move_assignable<T>::value来代替。

这两种指明不抛出异常的方法在外在行为上是一样的。 如果用noexcept运算符去探测noexcept和throw()声明的函数,会返回相同的结果。

但实际上在C++11标准中,它们在实现上确实是有一些差异的。

如果一个函数在声明了noexcept的基础上抛出了异常,那么程序将不需要展开堆栈,

并且它可以随时停止展开。另外,它不会调用std::unexpected,

而是调用std::terminate结束程序。而throw()则需要展开堆栈,

并调用std::unexpected。这些差异让使用noexcept程序拥有更高的性能。

在C++17标准中,throw()成为noexcept的一个别名,也就是说throw()和noexcept拥有了同样的行为和实现。

另外,在C++17标准中只有throw()被保留了下来,其他用throw声明函数抛出异常的方法都被移除了。

在C++20中throw()也被标准移除了,使用throw声明函数异常的方法正式退出了历史舞台。总之现代C++只是用noexcept别使用throw()就行了。

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

using namespace std;

void foo() throw()

{

throw std::runtime_error("hi mom");

}

void my_unexpected_handler()

{

std::cout << "my_unexpected_handler" << std::endl;

std::terminate();

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

std::set_unexpected(my_unexpected_handler);

try

{

foo();

}

catch (const std::runtime_error &e)

{

std::cerr << e.what() << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

// foo()后 使用throw() 会 std::unexpected(); 触发 my_unexpected_handler 然后core

// foo()后 使用noexcept 会直接coreC++11 标准规定下面几种函数会默认带有noexcept声明。

Ⅰ 默认构造函数、默认复制构造函数、默认赋值函数、默认移动构造函数和默认移动赋值函数。

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base

{

public:

Base() noexcept

{

}

Base(const Base &other) noexcept

{

cout << "Base(const Base &other)" << endl;

}

Base &operator=(const Base &other)

{

return *this;

}

};

class A : Base

{

public:

A() = default;

A(const A &other) : Base(other)

{

cout << "A(const A &other)" << endl;

}

A &operator=(const A &other)

{

Base::operator=(other);

return *this;

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A a;

A a1(a);

// Base(const Base &other)

// A(const A &other)

cout << noexcept(A()) << endl; // 1

cout << noexcept(A(A())) << endl; // 1

cout << noexcept(A().operator=(A())) << endl; // 0

return 0;

}有一个额外要求,对应的函数在类型的基类和成员中也具有noexcept声明,否则其对应函数将不再默认带有noexcept声明。 另外,自定义实现的函数默认也不会带有noexcept声明:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

struct X

{

};

#define PRINT_NOEXCEPT(x) \

std::cout << #x << "=" << x << std::endl;

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

X x;

cout << std::boolalpha;

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(X())); // 默认构造函数

// noexcept(X())=true

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(X(x))); // 默认拷贝构造函数

// noexcept(X(x))=true

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(X(std::move(x)))); // 默认移动构造函数

// noexcept(X(std::move(x)))=true

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(x.operator=(x))); // 默认赋值函数

// noexcept(x.operator=(x))=true

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(x.operator=(std::move(x)))); // 默认移动赋值函数

// noexcept(x.operator=(std::move(x)))=true

return 0;

}如果在X中嵌入一个M,X没有自定义实现各函数,如调用默认构造函数时也会调用M的默认构造函数,M的相关函数是否为noexcept也会影响X;

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

struct M

{

M() {}

M(const M &) {}

M(M &&) noexcept {}

M operator=(const M &) noexcept { return *this; }

M operator=(M &&) { return *this; }

};

struct X

{

M m;

};

#define PRINT_NOEXCEPT(x) \

std::cout << #x << "=" << x << std::endl;

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

X x;

cout << std::boolalpha;

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(X())); // 默认构造函数

// noexcept(X())=false

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(X(x))); // 默认拷贝构造函数

// noexcept(X(x))=false

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(X(std::move(x)))); // 默认移动构造函数

// noexcept(X(std::move(x)))=true

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(x.operator=(x))); // 默认赋值函数

// noexcept(x.operator=(x))=true

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(x.operator=(std::move(x)))); // 默认移动赋值函数

// noexcept(x.operator=(std::move(x)))=false

return 0;

}Ⅱ 类型的析构函数以及delete运算符默认带有noexcept声明, 请注意即使自定义实现的析构函数也会默认带有noexcept声明, 除非类型本身或者其基类和成员明确使用noexcept(false)声明析构函数, 以上也同样适用于delete运算符:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

struct M

{

~M() noexcept(false) {}

};

struct X

{

};

struct X1

{

~X1() {}

};

struct X2

{

~X2() noexcept(false) {}

};

struct X3

{

M m;

};

#define PRINT_NOEXCEPT(x) \

std::cout << #x << " = " << x << std::endl

int main()

{

X *x = new X;

X1 *x1 = new X1;

X2 *x2 = new X2;

X3 *x3 = new X3;

std::cout << std::boolalpha;

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(x->~X())); // true

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(x1->~X1())); // true

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(x2->~X2())); // false

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(x3->~X3())); // false

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(delete x)); // true

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(delete x1)); // true

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(delete x2)); // false

PRINT_NOEXCEPT(noexcept(delete x3)); // false

return 0;

}可以看出noexcept运算符对于析构函数和delete运算符有着同样的结果。

自定义析构函数X1()依然会带有noexcept的声明,除非如同X2()显示的声明noexcept(false)。

X3有一个成员变量m,其类型M的析构函数被声明为noexcept(false),这使X3的析构函数也被声明为noexcept(false)。

什么时候使用noexcept是一个关乎接口设计的问题。原因是一旦我们用noexcept声明了函数接口, 就需要确保以后修改代码也不会抛出异常,不会有理由让我们删除noexcept声明。这是一种协议, 试想一下,如果客户看到我们给出的接口使用了noexcept声明,他会自然而然地认为“哦好的,这个函数不会抛出异常, 我不用为它添加额外的处理代码了”。如果某天,我们迫于业务需求撕毁了协议,并在某种情况下抛出异常, 这对客户来说是很大的打击。因为编译器是不会提示客户,让他在代码中添加异常处理的。 所以对于大多数函数和接口我们应该保持函数的异常中立。那么哪些函数可以使用noexcept声明呢? 这里总结了两种情况。

除了上述两种理由,我认为保持函数的异常中立是一个明智的选择,因为将函数从没有noexcept声明修改为带noexcept声明并不会付出额外代价,而反过来的代价有可能是很大的。

在C++17标准之前,异常规范没有作为类型系统的一部分,所以下面的代码在编译阶段不会出现问题:

#include <iostream>

#include <type_traits>

using namespace std;

void (*fp)() noexcept = nullptr;

void foo() {}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

// --std=c++11 => 1

// --std=c++17 => 0

cout << std::is_same<decltype(fp), decltype(&foo)>::value << endl;

return 0;

}在上面的代码中fp是一个指向确保不抛出异常的函数的指针,而函数foo则没有不抛出异常的保证。在C++17之前,它们的类型是相同的,也就是说std::is_same<decltype(fp),decltype(&foo)>::value返回的结果为true。

显然,这种宽松的规则会带来一些问题,例如一个会抛出异常的函数通过一个保证不抛出异常的函数指针进行调用,结果该函数确实抛出了异常,正常流程本应该是由程序捕获异常并进行下一步处理,但是由于函数指针保证不会抛出异常,因此程序直接调用std::terminate函数中止了程序:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void (*fp)() noexcept = nullptr;

void foo()

{

throw(5);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

fp = &foo;

try

{

fp();

}

catch (int e)

{

cout << e << endl;

}

return 0;

}以上代码预期中的运行结果应该是输出数字5。但是由于函数指针的使用不当, 导致程序意外中止并且只留下了一句:“terminate called after throwing an instance of ‘int’”。但是实测有些编译器C++11是会输出5的。

为了解决此类问题,C++17标准将异常规范引入了类型系统。这样一来,fp = &foo就无法通过编译了,因为fp和&foo变成了不同的类型,std::is_same <decltype(fp), decltype(&foo)>::value会返回false。值得注意的是,虽然类型系统引入异常规范导致noexcept声明的函数指针无法接受没有noexcept声明的函数,但是反过来却是被允许的,比如:

void(*fp)() = nullptr;

void foo() noexcept {}

int main()

{

fp = &foo;

}这里的原因很容易理解,一方面这个设定可以保证现有代码的兼容性,旧代码不会因为没有声明noexcept的函数指针而编译报错。另一方面,在语义上也是可以接受的,因为函数指针既没有保证会抛出异常,也没有保证不会抛出异常,所以接受一个保证不会抛出异常的函数也合情合理。同样,虚函数的重写也遵守这个规则,例如:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base

{

public:

virtual void foo() noexcept {}

};

class Derived : public Base

{

public:

void foo() override{}; // 编译错误

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

return 0;

}以上代码无法编译成功,因为派生类试图用没有声明noexcept的虚函数重写基类中声明noexcept的虚函数,这是不允许的。 但反过来是可以通过编译的:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base

{

public:

virtual void foo() {}

};

class Derived : public Base

{

public:

void foo() noexcept override{};

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

return 0;

}最后需要注意的是模板带来的兼容性问题,在标准文档中给出了这样一个例子:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void g1() noexcept {}

void g2() {}

template <class T>

void f(T *, T *) {}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

// void f<void ()>(void (*)(), void (*)())

f(g1, g2);

return 0;

}

// --std=c++11 可以编译通过

// --std=c++17 error: no matching function for call to 'f(void (&)() noexcept, void (&)())'可以改为

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void g1() noexcept {}

void g2() {}

template <class T1, class T2>

void f(T1 *, T2 *) {}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

f(g1, g2);

return 0;

}函数指针

//example14.cpp

void func() noexcept

{

}

void func1() noexcept(false)

{

throw runtime_error("");

}

void (*ptr1)() noexcept = func; // func与ptr都承诺noexcept

void (*ptr2)() = func; // func为noexcept ptr不保证noexcept

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

ptr1 = func1; //不能像except的赋给nnoexcept函数指针

ptr2 = func1;

return 0;

}虚函数,如果基类虚方法为 noexcept 则派生类派生出的也为 noexcept,如果基类为 except 的则派生类可以指定非 noexcept 或者 noexcept

//example15.cpp

class A

{

public:

virtual void f1() noexcept;

virtual void f2() noexcept(false);

virtual void f3(); //默认为noexcept(false)

};

class B : public A

{

public:

void f1() noexcept override

{

}

void f2() noexcept override

{

}

void f3() noexcept override

{

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

B b;

b.f1(), b.f2(), b.f3();

return 0;

}

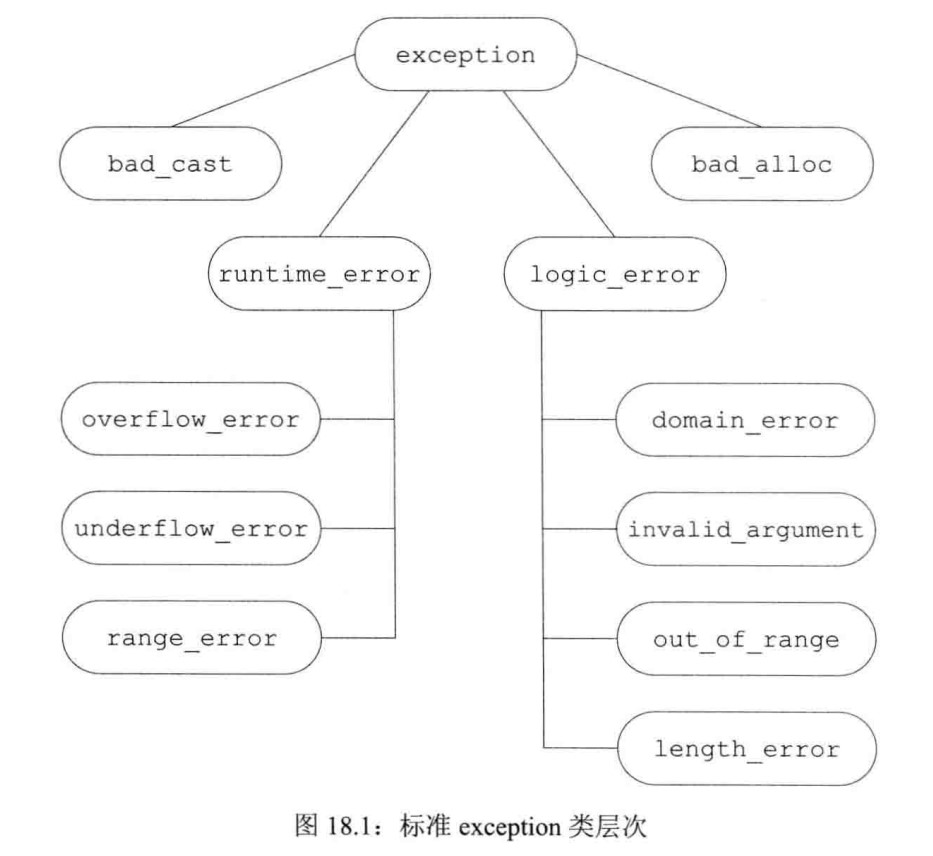

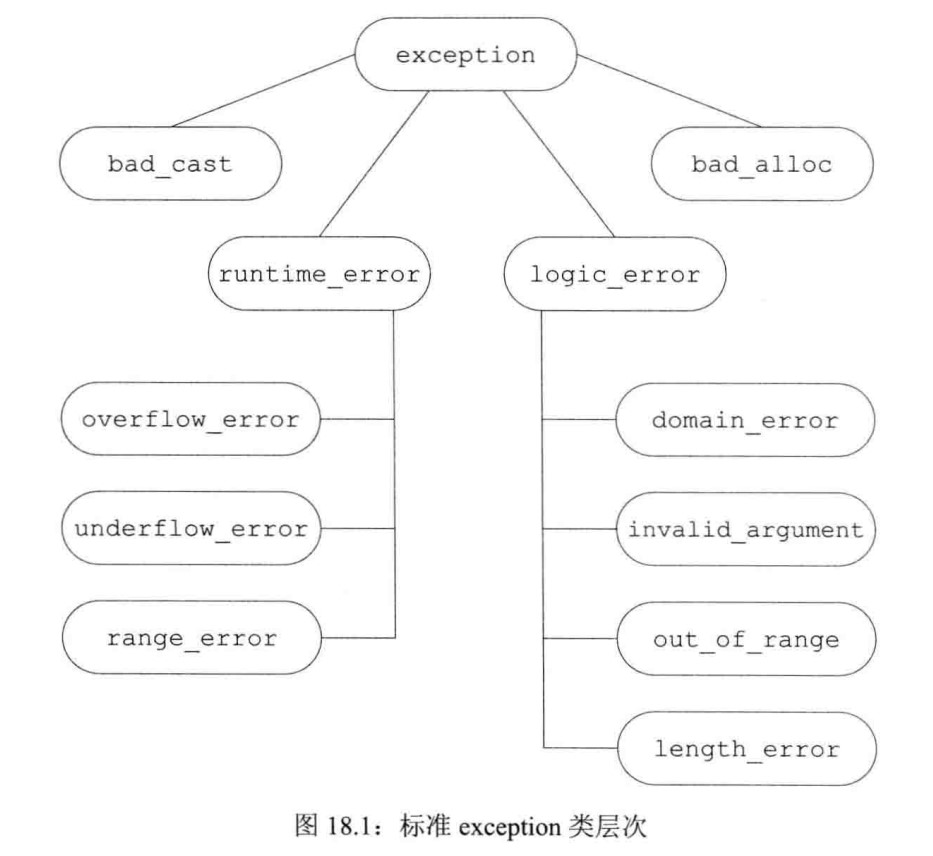

exception 只定义了拷贝构造函数、拷贝赋值运算符、虚析构函数、what

的虚成员,what 返回 const char* 字符数组,其为 noexcept(true)的

exception、bad_cast、bad_alloc

有默认构造函数、runtime_error、logic_error 无默认构造函数,可以接收 C

字符数组

编写的异常类其的根基类为 exception

//example16.cpp

class MException : public std::runtime_error

{

public:

int number;

MException(const string &s) : runtime_error(s), number(0)

{

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

try

{

MException e("oop");

e.number = 999;

throw e;

}

catch (MException &e)

{

cout << e.number << endl; // 999

cout << e.what() << endl; // oop

}

return 0;

}如果一个异常在代理构造函数的初始化列表或主体中被抛出,那么委托构造函数的主体将不再被执行,控制权会交到异常捕获的 catch 代码块中

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class X

{

public:

X()

try : X(0)

{

cout << "X()" << endl;

}

catch (int e)

{

cout << "catched " << e << endl;

throw 3;

}

X(int a)

try : X(a, 0.)

{

cout << "X(int a)" << endl;

}

catch (int e)

{

cout << "catched " << e << endl;

throw 2;

}

X(double b) : X(0, b) {}

X(int a, double b) : a_(a), b_(b)

{

cout << "X(int a, double b)" << endl;

throw 1;

}

private:

int a_;

double b_;

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

try

{

X x;

}

catch (int e)

{

cout << "catched " << e << endl;

}

return 0;

}

/*

X(int a, double b)

catched 1

catched 2

catched 3

*/如果在X(int a,double b)中没有 throw,那么则会输出

X(int a, double b)

X(int a)

X()当多个不同的库在一起使用时,及那个名字放置在全局命名空间中将引起命名空间污染,还有可能造成重复定义等。在

C

中往往使用命名加前缀从定义的名称上来解决,C++中引入了命名空间的概念

可以使得一个库中的内容更加封闭,不会与其他的内容出现名字冲突

关键词namespace,随后为命名空间的名称,然后为花括号。花括号内主要包括,类、变量(及其初始化操作)、函数(及定义)、模板、其他命名空间

//example17.cpp

namespace me

{

class Person

{

public:

int age;

Person(int age) : age(age) {}

};

int num = 999;

void func()

{

cout << num << endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

me::func(); // 999

cout << me::num << endl; // 999

me::Person person(me::num);

cout << person.age << endl; // 999

return 0;

}要注意的是,命名空间作用域后面无须分号

每个命名空间是一个独立的作用域,作用域与作用域之间不会产生命名冲突

//example18.cpp

namespace A

{

int num = 999;

}

namespace B

{

int num = 888;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

cout << A::num << " " << B::num << endl; // 999 888

return 0;

}namespace 是可以进行重新打开的,并不需要在一个花括号内定义或声明 namespace 的全部内容

//example19.cpp

namespace A

{

int n1 = 999;

}

namespace A

{

int n2 = 888;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

cout << A::n1 << " " << A::n2 << endl; // 999 888

return 0;

}通常头文件中命名空间中定义类以及声明作为类接口的函数及对象,命名空间成员的定义置于源文件中

与类的声明定义规范非常相似

//example20/main.hpp

#pragma once

namespace A

{

class Data

{

public:

int num;

Data(const int &num) : num(num)

{

}

void print();

};

}//example20/main.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "main.hpp"

using namespace std;

namespace A

{

void Data::print()

{

cout << num << endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::Data data(21);

data.print(); // 21

return 0;

}完全允许在 namespace 作用域外定义命名空间成员,但是要显式指出命名空间

//example21.cpp

namespace A

{

void print();

}

void A::print()

{

cout << "hello world" << endl;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::print(); // hello world

return 0;

}或者重新打开命名空间等

//example22.cpp

namespace A

{

void print();

}

namespace A

{

void print()

{

cout << "hello world" << endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::print(); // hello world

return 0;

}在模板章节中,已经有使用过定义模板特例化,模板特例化必须定义在原始模板所属的命名空间中

//example23.cpp

class Person

{

public:

int num;

};

//打开命名空间std

namespace std

{

template <>

struct hash<Person>;

}

//定义

template <>

struct std::hash<Person>

{

size_t operator()(const Person &p) const

{

return std::hash<int>()(p.num);

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

Person p;

p.num = 888;

cout << std::hash<Person>()(p) << endl; // 888

return 0;

}全局命名空间也就是整个全局作用域,全局作用域是隐式的,所以它没有自己的名字

//example24.cpp

int num = 999;

void func()

{

cout << num << endl;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

::num = 888;

::func(); // 888

return 0;

}命名空间里面可以有命名空间,也就形成了命名空间的嵌套

//example25.cpp

namespace A

{

namespace B

{

int num = 888;

}

namespace C

{

void print();

}

}

void A::C::print()

{

cout << B::num << endl;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::B::num = 666;

A::C::print(); // 666

return 0;

}在 C++17 中支持简洁的定义嵌套命名空间的方法

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

namespace A

{

namespace B

{

namespace C

{

void func();

}

}

}

namespace A::B::C

{

void func()

{

std::cout << "A::B::C" << std::endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::B::C::func(); // A::B::C

return 0;

}#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

namespace A::B::inline C

{

void func();

}

namespace A::inline D::E

{

void func();

}

void A::B::C::func()

{

std::cout << "A::B::C::func" << std::endl;

}

void A::D::E::func()

{

std::cout << "A::D::E::func" << std::endl;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::B::func(); // A::B::C::func

A::B::C::func(); // A::B::C::func

A::E::func(); // A::D::E::func

A::D::E::func(); // A::D::E::func

return 0;

}内联命名空间(inline namespace)是 C++11 引入的一种新的嵌套命名空间,在 namespace 前加上 inline 可以将命名空间内的东西范围提到父命名空间内

//example26.cpp

inline namespace A

{

int num = 999;

}

namespace A

{

void print()

{

cout << num << endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

//通过namespaceA的外层空间的名字即可访问A的num

cout << ::num << endl; // 999

A::print();

//但仍可以指定A::

cout << A::num << endl; // 999

::print(); // 999

return 0;

}重点:关键字 inline 必须出现在命名空间第一次定义的地方,后续再次打开可以些 inline 也可以不写

内联命名空间支持嵌套

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

namespace A

{

namespace child2

{

void func();

}

inline namespace child1

{

void func();

}

}

void A::child2::func()

{

std::cout << "child2" << std::endl;

}

void A::child1::func()

{

std::cout << "child1" << std::endl;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::func(); // child1

A::child1::func(); // child1

A::child2::func(); // child2

return 0;

}一种骚操作的写法

//example27/A.hpp

#pragma once

inline namespace A

{

int num = 999;

string name = "gaowanlu";

}//example27/B.hpp

#pragma once

inline namespace B

{

int num = 888;

}//example27/main.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

namespace C

{

#include "A.hpp"

#include "B.hpp"

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

cout << C::A::num << endl; // 999

cout << C::B::num << endl; // 888

// cout << C::num << endl;//错误

cout << C::name << endl; // gaowanlu

return 0;

}未命名的命名空间(unnamed namespace)定义的变量拥有静态生命周期,在第一次使用前创建,并且 直到程序结束才销毁

重点:未命名的命名空间仅在特定的文件内部有效,其作用范围不会横跨多个不同的文件

//example28.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int i = 999; //此i是跨文件作用域的

namespace

{

int i = 888; //此i只在此cpp中有效

}

//在C中往往使用static达到此目的,但C++标准中已经取消了,推荐使用未命名的命名空间

static int num = 666; // num仅在此文件有效

namespace A

{

namespace

{

int i; //在命名空间A中

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

// cout << i << endl;//错误 出现二义性 编译器不知道是哪一个i

cout << num << endl; // 666

A::i = 888;

cout << A::i << endl; // 888

return 0;

}使用命名空间的成员就要显式在前面指出命名空间,这样的操作往往会显得繁琐,例如使用标准库中的 string 每次都要在前面指定 std::,这样将会过于麻烦,我们已经知道有 using 这样的操作,下面将会深入学习 using

可以将 namespace 当做数据类型来为 namespace 定义新的名字

//example29.cpp

namespace AAAAA

{

int num = 666;

namespace B

{

int num = 999;

}

}

namespace

{

namespace A = AAAAA;

namespace AB = AAAAA::B;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::num = 888;

cout << A::num << endl; // 888

cout << AB::num << endl; // 999

return 0;

}using

声明语句可以出现在全局作用域、局部作用域、命名空间作用域以及类的作用域中

一条 using 声明语句一次只能引入命名空间的一个成员

//example30.cpp

namespace A

{

using std::string;

string name;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::name = "gaowanlu";

std::cout << A::name << std::endl; // gaowanlu

{

using std::cout;

using std::endl;

cout << A::name << endl; // gaowanlu

}

return 0;

}using namespace xx,using 指示一次引入命名空间全部成员

using

指示可以出现在全局作用域、局部作用域、命名空间作用域中,不能出现在类的作用域中

//example31.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int i = 999;

namespace A

{

using namespace std;

int i = 888;

string name;

void print()

{

cout << name << endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::name = "gaowanlu";

A::print(); // gaowanlu

using namespace A;

// cout << i << endl;//二义性

cout << A::i << endl; // 888

cout << ::i << endl; // 999

return 0;

}在前面的章节我们也有提到,不应该再头文件中的全局作用域部分使用

using,因为头文件会被引入到源文件中,造成源文件不知不觉的使用了

using

所以头文件最多只能在它的函数或命名空间内使用 using 指示或 using 声明

在 namespace 嵌套的情况下,往往容易混淆对作用域的理解

//example32.cpp

namespace A

{

int i = 666;

namespace B

{

int i = 777;

void print1()

{

cout << i << endl;

}

void print2()

{

int i = 999;

cout << i << endl;

}

}

void print1()

{

// cout << h << endl;//// error: 'h' was not declared in this scope

}

void print2();

int h = 999;

}

void A::print2()

{

cout << h << endl;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::B::print1(); // 777

A::B::print2(); // 999

A::print2(); // 999

return 0;

}当 namespace 中定义类时

//example33.cpp

namespace A

{

int i = 888;

class B

{

public:

int i = 999;

void print()

{

cout << i << endl;

// cout << h << endl;// error: 'h' was not declared in this scope

}

};

void print1()

{

// cout << h << endl;// error: 'h' was not declared in this scope

}

int h = 555;

void print2()

{

cout << h << endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::B b;

b.print(); // 999

A::print2(); // 555

return 0;

}可见 namespace 中的定义的现后顺序会影响其使用,在使用前必须要已经定义过了

//example34.cpp

#include <iostream>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

{

std::string s;

std::cin >> s; //等价于

std::cout << s << std::endl;

operator>>(std::cin, s);

std::cout << s << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}这里面有什么关于 using 的知识呢?operator>>在 std 命名空间内,为什么没有显式指出 std 就可以调用了呢,因此除了普通的命名空间作用域查找,还会查找其实参所在的命名空间,所以实参 cin 在 std 内,所以会在 std 中查找时找到,所以调用了 std::operator>>

当然可以依旧显式的指出

//example35.cpp

#include <iostream>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

{

using std::operator>>;

std::string s;

operator>>(std::cin, s);

}

{

std::string s;

std::operator>>(std::cin, s);

}

return 0;

}在千前面有提到,使用 move 与 forward 时要使用 std::move 与

std::forward,而不省略

std。这是因为涉及到实参命名空间推断的问题,如果实参的命名空间中有 move

或者 forward 可能会造成意想不到的结果

约定,总是用 std::move 与 std::forard 就好了

一个另外的未声明的类或函数如果第一次出现在友元声明中,则认为它是最近的外层命名空间的成员

//example37.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void f2();

namespace A

{

class C

{

private:

int age = 999;

public:

//下面的友元隐式成为A的成员,编译器认为f f2定义在命名空间A中

friend void f2();

friend void f(const C &);

};

void f(const C &c)

{

cout << "f " << c.age << endl;

}

// void f2(){

// cout << "f2" << endl;

// }

}

void f2()

{

A::C c;

// cout << "f2 " << c.age << endl;

// error: 'int A::C::age' is private within this context

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::C c;

A::f(c); // f 999

// A::f2();//error: 'f2' is not a member of 'A'

f2();

return 0;

}不仅会向实参的命名空间查找,还会向实参基类所在的命名空间查找

//example38.cpp

namespace A

{

class B

{

};

void print(const B &b)

{

cout << "print" << endl;

}

}

class C : public A::B

{

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

C c;

print(c); // print

return 0;

}using 声明关注的是名字,而不关注参数列表

//example39.cpp

namespace A

{

void print()

{

cout << "print()" << endl;

}

void print(int n)

{

cout << "print(n)" << endl;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

// using A::print(int);//错误

using A::print; //正确

A::print(); // print()

A::print(12); // print(n)

return 0;

}using namespace 使得相应命名空间内的成员加入到候选集中

//example40/main.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

namespace A

{

extern void print(int);

extern void print(double);

}

void print(string s)

{

cout << s << endl;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

A::print(10); // 10

A::print(23.32); // 23.32

using namespace A;

print(10); // 10

print(23.32); // 23.32

print("sds"); // sds

return 0;

}

// g++ main.cpp other.cpp -o example40.exe当 main 使用 using namespace A;后在 main 中 print 有了三个候选项

//example40/other.cpp

#include <iostream>

namespace A

{

void print(int n)

{

std::cout << n << std::endl;

}

void print(double n);

}

void A::print(double n)

{

std::cout << n << std::endl;

}在一个作用域下,using 指示多个命名空间

//example41.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void print()

{

}

void print(int n)

{

cout << "global" << endl;

}

namespace A

{

int print(int n)

{

cout << n << endl;

return n;

}

}

namespace B

{

double print(double d)

{

cout << d << endl;

return d;

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

{

using namespace A;

using namespace B;

print(); //

// print(12); // 二义性

::print(12); // global

A::print(12); // 12

print(34.2); // 34.2

}

return 0;

}多重继承是指从多个直接基类中产生派生类的能力。

//example42.cpp

class A

{

public:

int a;

};

class B

{

public:

int b;

};

class C : public A, public B

{

public:

int c;

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

C c;

c.a = c.b = c.c = 999;

cout << c.a << " " << c.b << " " << c.c << endl; // 999 999 999

return 0;

}实际工程运用中并没有像这样简单

与单继承相同,在派生类构造函数初始化列表中可以使用基类的构造函数对相应基类进行初始化

//example43.cpp

class A

{

public:

int age;

string name;

A(const int &age, const string &name) : age(age), name(name) {}

};

class B

{

public:

B(const int &b) : b(b) {}

int b;

};

class C : public A, public B

{

public:

C(const int &age, const string &name, const int &b) : A(age, name), B(b)

{

//先初始化第一个直接基类A 然后初始化第二个直接基类B

}

void print();

};

void C::print()

{

cout << age << " " << name << " " << b << endl;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

C c(20, "gaowanlu", 1);

c.print(); // 20 gaowanlu 1

return 0;

}在 OOP 章节学习过单继承的继承构造函数,在 C++11 中,允许从多个直接基类继承构造函数(注意要注意二义性,继承两个相同函数签名的构造函数是不可行的)

//example44.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class A

{

public:

string s;

double n;

A() = default;

A(const string &s) : s(s)

{

}

A(double n) : n(n) {}

};

class B

{

public:

B() = default;

B(const string &s)

{

}

B(int n) {}

};

class C : public A, public B

{

public:

using A::A;

using B::B;

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

C c;

// C c("s");//错误不知道使用继承的哪一个构造函数A与B都是const string&

return 0;

}怎样解决这样的构造函数继承冲突,当自身定义了此形式的构造函数时,这个形式的构造函数就不会被继承

//example45.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class A

{

public:

string s;

double n;

A() = default;

A(const string &s) : s(s)

{

}

A(double n) : n(n) {}

};

class B

{

public:

B() = default;

B(const string &s)

{

}

B(int n) {}

};

class C : public A, public B

{

public:

using A::A;

using B::B;

C(const string &s) : B(s), A(s) {}

C() = default;

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

C c("s");

cout << c.A::s << endl; // s

return 0;

}当多继承时构造函数的执行顺序与析构函数执行顺序相反

//example46.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class A

{

public:

A()

{

cout << "A" << endl;

}

~A()

{

cout << "~A" << endl;

}

};

class B

{

public:

B()

{

cout << "B" << endl;

}

~B()

{

cout << "~B" << endl;

}

};

class C : public A, public B

{

public:

C()

{

cout << "C" << endl;

}

~C()

{

cout << "~C" << endl;

}

};

class D : public B, public A

{

public:

D()

{

cout << "D" << endl;

}

~D()

{

cout << "~D" << endl;

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

{

C c; // A B C

D d; // B A D

}

//从栈顶依次释放

//~D ~A ~B

//~C ~B ~A

return 0;

}如果派生类没有自定义拷贝与移动操作,编译器将会进行自动合成。并且其基类部分在拷贝或移动时会被基类部分使用基类的相关拷贝与移动操作。

同理如果自定义了相关操作,编译器则不再为其自动合成

//example47.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class A

{

public:

int a;

A(const int &a) : a(a)

{

}

};

class B

{

public:

int b;

B(const int &b) : b(b) {}

};

class C : public A, public B

{

public:

int c;

C(int a, int b, int c) : A(a), B(b), c(c)

{

}

void print()

{

cout << a << " " << b << " " << c << endl;

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

C c(1, 2, 3);

C c1 = c;

c.print(); // 1 2 3

return 0;

}基类的指针或引用可以直接指向一个派生类对象

//example48.cpp

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

// class C : public A, public B

C c(1, 2, 3);

//引用

C &cref = c;

B &bref = c;

A &aref = c;

cout << bref.b << " " << aref.a << endl; // 2 1

//指针

B *bptr = &c;

A *aptr = &c;

cout << bptr->b << " " << aptr->a << endl; // 2 1

//值

B b = c; //只保留基类部分进行拷贝

A a = c;

cout << b.b << " " << a.a << endl; // 2 1

return 0;

}当函数重载遇见多继承可能出现的问题

//example49.cpp

void print(A &a)

{

}

void print(B &b)

{

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

// class C : public A, public B

C c(1, 2, 3);

// print(c);//二义性

B &b = c;

print(b);

A &a = c;

print(a);

return 0;

}在单继承中,派生类部分找不到将会去往基类寻找按照继承链向上上找。在多重继承中派生类部分找不到,将会在其直接基类中同时查找,如果找到多个则出现二义性

//example50.cpp

class A

{

public:

int num;

A(const int &num) : num(num)

{

}

};

class B

{

public:

int num;

B(const int &num) : num(num) {}

};

class C : public A, public B

{

public:

C(int num) : A(num), B(num)

{

}

void print()

{

cout << A::num << " " << B::num << endl;

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

C c(12);

// cout << c.num << endl;//二义性

//解决方案

cout << c.A::num << endl; // 12 显式指定

cout << c.B::num << endl; // 12

c.print(); // 12 12

return 0;

}什么是虚继承?以上的这种多重继承方式,会出现一种问题,对然在直接基类中一个类只能出现依次,但是在整个继承链中,一个类可能会出现多次

//example51.cpp

class Person

{

public:

int age;

};

class Student : public Person

{

};

class Girl : public Person

{

};

class GirlFriend : public Girl, public Student

{

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

GirlFriend she;

// she.age;//二义性

she.Girl::age = 23;

she.Student::age = 43;

cout << she.Girl::age << endl;//23

cout << she.Student::age << endl;//43

return 0;

}虚继承就是为了解决这种问题的

虚继承的目的就是当出现 example51.cpp 中的问题时,怎样将在继承链中怎样将 Person 何为一个实例,而不是 Girl 部分与 Student 部分分别继承两个不同的 Person 实例

虚继承的使用方式就是在派生列表中添加 virtual 关键字

class A:public virtual B;

class A:virtual public B;解决 example51.cpp 中的问题

//example52.cpp

class Person

{

public:

int age;

};

class Student : public virtual Person

{

};

class Girl : public virtual Person

{

};

class GirlFriend : public Girl, public Student

{

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

GirlFriend she;

she.age = 23;

cout << she.age << endl;

//只有一个Person实例

she.Girl::Person::age = 43;

cout << she.Student::Person::age << endl; // 43

return 0;

}虚继承中派生类向基类的类型转换并不会受到影响

//example53.cpp

class Person

{

public:

int age;

};

class Student : public virtual Person

{

};

class Girl : public virtual Person

{

};

class GirlFriend : public Girl, public Student

{

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

Student student;

Person &p1 = student;

p1.age = 12;

cout << p1.age << endl; // 12

GirlFriend she;

Person *ptr = &she;

ptr->age = 20;

cout << ptr->age << endl; // 20

return 0;

}在单继承中,查找只当成员时,会从派生类本身部分查找,查找不到就沿着继承链向上查找。但使用了虚继承后,查找到同一个成员的路径不可不止一条,如在 example52.cpp 中,GirlFriend 部分找不到 age,向上查找有 Student 部分、Girl 部分,二者都又继承同一个 Person 实例,总之无论从哪一个查找 age 最终都是统一个实例

虚继承,虚基类只有一个实例,但是在其派生类的构造函数构造时调用了其构造函数,如果派生类使用构造函数不是相同的时候会怎样呢

//example54.cpp

class Person

{

public:

int age;

string name;

Person() = default;

Person(int age) : age(age) {}

Person(string name) : name(name) {}

};

class Student : public virtual Person

{

public:

Student() : Person(12) {}

};

class Girl : public virtual Person

{

public:

Girl() : Person("sdc") {}

};

class GirlFriend : public Girl, public Student

{

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

GirlFriend she;

cout << she.age << endl; //乱码

cout << she.name << endl; //""

//为什么两个构造都没有被成功执行

return 0;

}因为这样,不仅仅编译器蒙圈了,恐怕我们自己都有点蒙圈。以边让使用 Person(12)构造 Person 实例,一边让用 Person(“sdc”)构造 Person 实例,那么有没有解决办法呢?

//example55.cpp

class Person

{

public:

int age;

string name;

Person() = default;

Person(int age) : age(age)

{

cout << "Person" << endl;

}

Person(string name) : name(name)

{

cout << "Person" << endl;

}

};

class Student : public virtual Person

{

public:

Student() : Person(12)

{

cout << "Student" << endl;

}

};

class Girl : public virtual Person

{

public:

Girl() : Person("sdc")

{

cout << "Gril" << endl;

}

};

class GirlFriend : public Girl, public Student

{

public:

GirlFriend() : Student(), Girl(), Person(12)

{

cout << "GrilFriend" << endl;

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

GirlFriend she;

cout << she.age << endl; // 12

cout << she.name << endl; //""

/*

Person

Gril

Student

GrilFriend

*/

//派生类显式调用虚基类的构造函数后就创建了Person实例,在创建Stduent与Gril时不再构造Person

//直接将继承已经创建的Person实例

return 0;

}Note: 虚基类总是先于非虚基类构造,与它们在继承体系中的次序和位置无关

一个类可以继承多个虚基类,它们的构造顺序按照直接基类的声明顺序对其依次检查,确定其中是否含有虚基类,如有则先构造虚基类,然后按照声明顺序依次构造非虚基类

//example56.cpp

class A

{

public:

int a;

A(const int &a) : a(a)

{

cout << "A" << endl;

}

~A()

{

cout << "~A" << endl;

}

};

class B : public virtual A

{

public:

B() : A(12)

{

cout << "B" << endl;

}

~B()

{

cout << "~B" << endl;

}

};

class C

{

public:

C()

{

cout << "C" << endl;

}

~C()

{

cout << "~C" << endl;

}

};

class D : public B, public virtual C

{

public:

D() : A(13)

{

cout << "D" << endl;

}

~D()

{

cout << "~D" << endl;

}

};

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

{

D d; // A C B D

} //~D ~B ~C ~A

return 0;

}总之就是先构造虚基类,虚基类的构造顺序与在继承列表的顺序有关

至此我们学习完了第 18 章 用于大型程序的工具,主要为异常、命名空间、多重继承、虚继承。从第 1 章到第 18 章经历了千辛万苦,非常不容易。C++基础,基本剩余第 19 章 特殊工具与技术了,还有相关泛型算法的查阅表等附录内容。要坚持哦!